Part 4: Consequences

*

By William C. Shelton

(The opinions and views expressed in the commentaries of The Somerville Times belong solely to the authors of those commentaries and do not reflect the views or opinions of The Somerville Times, its staff or publishers)

An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics.

-Plutarch

Thus far in this series I have presented evidence regarding the extent of U.S. economic inequality and the reasons for its existence. But why should we care?

Health and wellbeing

Here is something fascinating that I learned from British epidemiologist Richard Wilkinson. Take any indicator of human wellbeing and look at how ratings on that factor change with the level of a country’s average national income per person. You will find that among market democracies with well-developed economies, there is no apparent relationship.

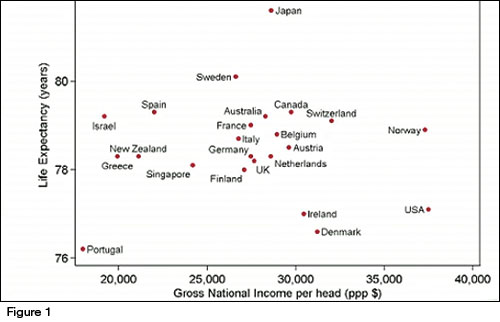

Figure 1, shows the results for life expectancy. Beyond a certain level of development, richer countries, as a group, do no better than poorer countries.

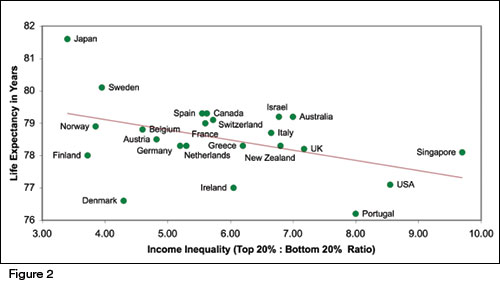

Now take those countries and compare their level of income inequality with the same wellbeing indicator. As Figure 2 illustrates, the more unequal the country is, the worse it does, regardless of how wealthy it is overall.

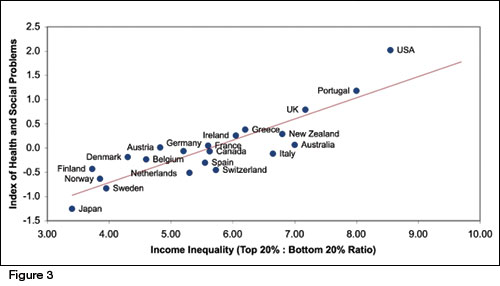

Wilkinson and his colleagues put together an index of health and social problems, equally weighting these factors: life expectancy, infant mortality, math and literacy scores, homicide rates, imprisonment rates, teenage births, levels of trust, mental illness, obesity, and social mobility. As Figure 3 shows, they found a tight correlation between their wellbeing index and inequality, the U.S. being the most unequal and enjoying the least wellbeing.

Comparing countries on any one of these factors reveals the same trend, and the differences aren’t small. Depending on the factor, the most unequal countries in the sample are between two and twenty times worse off than the least unequal.

You find the same relationship between inequality and wellbeing if you substitute American states for developed countries. The more economically unequal the states’ citizens are, the less healthy they are.

These differences don’t just affect the poor. The wealthiest people in the most equal societies, like Japan or Sweden, are healthier than their peers in the least equal societies, like the U.S. and the U.K.

The hypothesis that has the most supporting evidence to explain this finding has to do with the impacts of stress on physical, psychological, and social health. So far, 208 peer-reviewed studies have identified the kinds of stress that most reliably mobilize harmful hormones, like cortisol. They are those that involve threats to self-esteem or social status, and these increase with a society’s inequality.

Economic Growth

Since the Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher years, supply-siders have argued that extravagant compensation and low taxes for the wealthiest would spur economic growth. Thirty years on, it’s clear that George H.W. Bush was right when he called this “voodoo economics.”

It hasn’t worked for either the U.S. or Britain. Both have experienced lower economic growth, higher unemployment, and a more fragile economy, with deeper and more prolonged recessions.

The lower the share of national income that goes to middle- and low-income households, the less they can fuel the economy with their purchases. Henry Ford realized this in 1914 when he wrote that mass production could only realize its economic potential with policies “making 20,000 men prosperous and contented rather than following the plan of making a few slave-drivers in our establishment multi-millionaires.”

This is even truer today. During the era of voodoo economics, consumption has gone from representing a third of the U.S. economy to accounting for 70%, while workers have less income with which to sustain consumption. Many tried to compensate for income loss by borrowing against their homes. But the bursting housing bubble ushered in the Great Recession.

In the absence of growing consumer spending, CEOs look to boost profits by cutting costs, which most often means cutting jobs. Why not? Disciplined by economic anxiety, American employees work harder than those in any other developed country.

Wealthy corporations and individuals have not, as economic “conservatives” promised, invested their enormous gains in job-creating, economy expanding enterprises. Witness the mountains of cash sitting on corporate balance sheets and in individuals’ offshore tax havens.

I was taught in business school that cash is your least productive asset. But that’s not so if you’re a corporation that’s big enough to realize more profit through tax avoidance than through productive economic activity. Microsoft, for example, bought Skype and Nokia to avoid the taxes they would have paid if they had brought that cash back to the U.S.

Concentrating wealth among elites concentrates power as well, enabling them to buy the public policies that enable continued concentration of wealth and power.

Democracy

We can have a democracy, or great wealth in the hands of a few people, but we can’t have both.

– Justice Lewis Brandeis

We like to believe that America was conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all people are created equal, by which we mean equality of opportunity, not of outcome. But concentration of wealth has undermined this moral justification.

Pressures from special interest groups and the abiding hunger to be reelected constrain presidents’ and congressmen’s, mayors’ and aldermen’s ability to conceive, much less implement, egalitarian policy changes. At every level, those with the most money buy campaigns for their candidates and, through lobbying and media influence, buy legislative and administrative decisions.

Past feeble efforts to reform campaign finance merely directed money down other influence-buying paths. But in recent years, Supreme Court decisions and Internal Revenue Act amendments have unequivocally made our elected officials the best that money can buy.

Instead of reciting the obscene amounts of cash that moneyed interests “invest” in their favored candidates, I’d rather make this point: They can have enormous influence without spending a dime. The implied threat of financing an opponent can constrain an incumbent’s behavior. And of course, the fact that half of Congress is millionaires might make policies that favor the wealthy seem more reasonable to them.

Lobbyists can be as influential as campaign contributors, but less visible to the public. Legislative and administrative changes that weakened the regulation of financial services firms led directly to the Great Recession. In the six years before the financial meltdown, that industry alone spent $2.6 billion on lobbying, probably their most profitable investment.

The Wall Street Journal markets itself as “the daily diary of the American Dream.” A few years back, its investigative reporters did an excellent series on class. Among their findings was this: “Despite the widespread belief that the U.S. remains a more mobile society…in recent decades the typical child starting out in poverty in continental Europe (or in Canada) has had a better chance at prosperity.”

Those who yearn to live the American dream would be well advised to move to Scandinavia.

Reader Comments