Reviewed by Alan Kaufman

Because of my anthology, The Outlaw Bible of American Poetry, I am inundated by hopeful books of poetry, not to speak of the occasional slender volume that I purchase in bookstores, having read a rave review about it.

Reviewed by Alan Kaufman

Because of my anthology, The Outlaw Bible of American Poetry, I am inundated by hopeful books of poetry, not to speak of the occasional slender volume that I purchase in bookstores, having read a rave review about it.

The bulk of such titles I march down to the used bookstore, to trade for credit. Others, failing to prop up my soul serve to prop up the sofa, which is missing a leg (I’d throw it out if not for my Husky, Sloane, who lies enthroned upon it.)

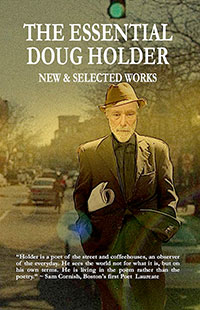

The Essential Doug Holder: New and Selected Poems is too enjoyable to part with just yet, and too important not to be archived and preserved. So, after it remains with me for a time, I’ll forward it for inclusion in The Alan Kaufman Papers in the Special Collections of The University of Delaware, thus ensuring that, at the very least, so long as there exists a State of Delaware, Doug Holder’s poems will endure.

They must survive. They are important. Their impact instantaneous, their mastery clear. You go back, sometimes repeatedly wondering at how it is possible in a few lines of verse to have landed a KO punch so deceptively?

When coming out of his corner, Holder sports an easy shuffling style, spars with you gently, does a little footwork. Then bang, you’re on the mat blinking up at the referee. The cumulative effect of a Holder poem is a bit fiendish, capped with lightening. There are poets like that. James Wright in the collections The Branch Will Not Break and Let Us Gather At the River; Sylvia Plath in her breakthrough volume, Ariel (especially the poem ‘Daddy’); Allen Ginsberg in the volume, HOWL and other poems; W.H. Auden in such classic poems as ‘In Memory of W.B. Yeats’ and “September 1, 1939.

In ‘Daddy, Is He A Monster?” , the first title in Holder’s ‘Collected’, a kid traveling on a bus spies the poet’s head “poking out of a protective shell of newspaper/ a suspicious crab” and asks his father: “Is he a monster?” Holder, “bloodshot eyes squinting/behind a shield of dark glass/the top of my head devoid of hair” forces a smile. In response, the kid ducks behind his seat, screaming.

Holder, who resides in Cambridge, Massachusetts, plys a gambit worthy of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Grasping that behind a child’s curiosity lurks self-preservation, an intuition of the lurking potential for evil in all things, Holder forces a smile that just for an instant tears away reality’s mask. The child’s terrified response offers a scathing commentary on life: he vanishes. It begs the question: how many of us, confronted with life’s terror, similarly disappear?

Or, take “A Moose In Boston”. What Holder sees trot down Commonwealth Avenue is not Bullwinkle but a regal creature “with patrician bearing” that strides with “the precision of dancer’s legs”, peering at human faces behind shop windows as if strolling through “a museum of surprise.” This is lovely writing. The last we see of this lordly visitation are the “persistent flies” of “the police/hot on its tail”.

In an ironic twist worthy of his own verse, Holder worked for years in the McLean’s Psychiatric Hospital, a landmark institution renowned for a client list of mentally ill versifiers that included Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton. Their peer in literary merit, yet Holden may be the only living poet associated with McLean who locked you into the straitjacket, rather than to wear it.

McLean Psychiatric Hospital.

In ‘3A.M. on the Psychiatric Ward’ Holder, walking the nighttime corridors of McLean’s with a flashlight, is aggressed by a stark naked female patient. “Her eyes beamed/sensitive as a doe’s–/then she lunged for me–/I grabbed both of her arms/and we did our strange dance/ anointed by moonlight from the barred window/tripping the light fantastic–/I was frightened and thrilled,/as she took the lead.”

The poem’s wry wit echoes Theodore Roethke’s ‘My Poppa’s Waltz’ in which the young Roethke’s drunken father comes home: “The whiskey on your breath/Could make a small boy dizzy/But I hung on like death/Such waltzing was not easy.” Both portray, with a mordant sense of humor, the frightening intimacy of irrational violence.

It some of his poems, Holder, who is Jewish, sounds schmaltzy subjects common to some Jewish writing—hot dogs, grandma, the Yankees, pickles, the Bronx. As the author of a memoir, Jew Boy, that tightrope walked over similar subjects–successfully, I hope–I am aware of the pitfulls of tackling such iconic cliches. With deft skill and an unfailing eye–and without abandoning Hamish values or virtues– Holder elevates such familiars into sharp, new vehicles for meaning and transcendence.

In ‘The Last Hot Dog’ he bears witness to the dying of his friend Sy Baum, who, as a last wish, requests a hot dog. Watching him struggle to eat, Holder sees rise “The mysterious, darkened delicatessens/under the elevated tracks/The Bronx gray afternoons/dining with his father./The sullen/ colorless meals/ though the franks/fully garnished, the bright yellow and green of mustard and relish. He swallowed hard/it was all/too much/to digest.” In one particularly devastating poem, ‘Where Is My Pocketbook?’, the ravages of old age are mercilessly portrayed: “I’ve lived enough—I’ve done it all.”/ She clutches her pocketbook/a weathered bag/to her weathered face./ Now it is resting/on her deflated breasts.’/”This is unfair, I want to die!”/ The light dims/ as evening surrenders/she screams shrilly/at the institutional walls/”Where is my pocketbook!” And further along: “Her fingers/move/like an arthritic snake/in search for/a flimsy thread/ to hold on./”Why must I suffer?/Let me go.” The poem is almost biblical in its sonorous sorrow, but with a touch of Samuel Beckett in the spareness of the character depiction, the starkly set scene.

In his best work, Holder overlays an avant garde modernist scrim of unsparing concrete detail over the banalities of life, making his poems impossible to put down. Without Beat theatrics or Rimbaud-like behavioral extremes, yet somehow they shock us into recognition of the extraordinary beauty and terror to be found in the numbing, unavoidable commonplaces that assail our daily lives.

Like WC Williams, or Charles Resnikoff, Doug Holder opens himself nakedly to Life and gives us its poetry, unadorned and remarkable.

Alan Kaufman is author of the critically-acclaimed memoir Jew Boy (Cornell University Press) as well as the novels Matches (Little Brown), The Berlin Woman (Mandel Vilar) , and a second memoir, Drunken Angel (Viva Editions/Simon and Schuster). His other books include several anthologies, including The Outlaw Bible of American Poetry (Basic Books/Hachette), The Outlaw Bible of American Art (Last Gasp), The Outlaw Bible of American Literature, coedited with Barney Rosset (Thunder’s Mouth Press) and The Outlaw Bible of American Essays (Basic Books/Hachette). A painter as well, his works are in the collections of The University of Delaware and private collections in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York City and Israel.

His writings have been included in many anthologies, including ALOUD: Voices from the Nuyorican Poets Cafe (Henry Holt) and Nothing Makes You Free: Writings from Descendants of Holocaust Survivors (WW Norton), while his essays and op-eds on culture and politics have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, Partisan Review, Evergreen Review and numerous other publications online and in print.

A broad selection of his books, manuscripts, paintings, drawings, notebooks, photographs and marginalia are available to be seen in The Alan Kaufman papers in the special Collections library of the University of Delaware.

http://www.lib.udel.edu/ud/spec/findaids/html/mss0599.html

Reader Comments