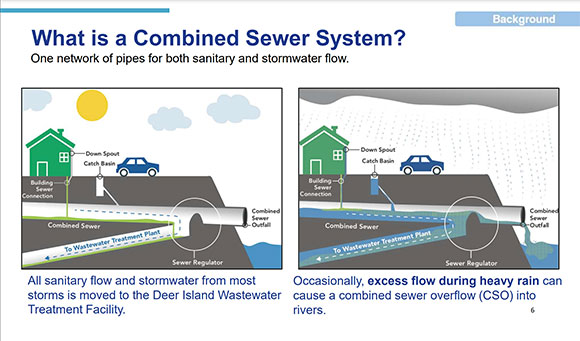

Slide from the presentation to the City Council explaining the combined sewer system.

By Jeffrey Shwom

A multi-generational approach to separate unsanitary water from stormwater is taking time and could cost hundreds of millions of dollars. The problem is “more than just combined sewer overflows (CSO) … the flooding is caused by runoff and hydraulic capacity of the brook,” Director of Infrastructure and Asset Management Rich Raiche discussed with the Somerville City Council on Thursday, May 22.

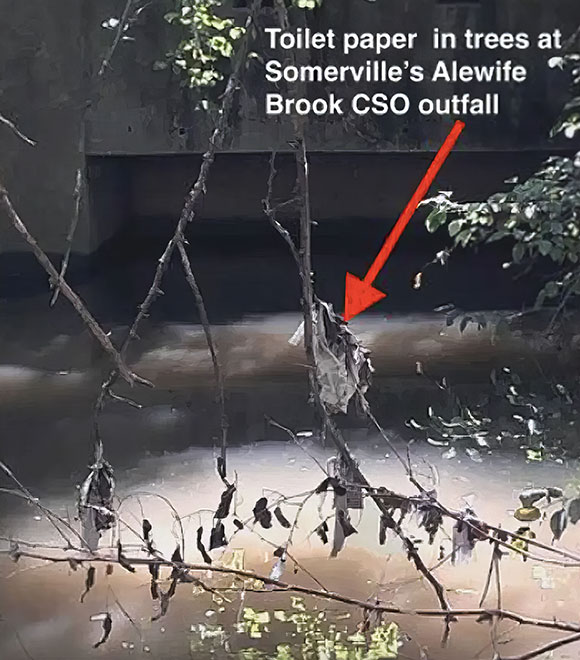

Advocacy group Save the Alewife Brook spokesperson Kristin Anderson said recent efforts to decrease the number of days untreated sewage overflows into local rivers and streams are not enough. “Alewife Brook floods regularly, sending raw sewage flood water over the banks of the brook and into the (Department of Conservation) park, its multi-use path, and into the yards and homes of area residents,” Anderson shared via email.

To fix the city’s historically separated sewer system and reduce the amount of impervious surfaces like pavement and houses, it could cost between $550 and $850 million over a 40 to 50-year period. Not to mention the estimated $1,200 per household cost of the current annual maintenance projects through fiscal year 2030. Anderson asked the city to find other money to solve the problem.

Somerville has made progress over the years. Raiche touted the number of city discharge points was reduced from eight to two three decades ago, and he worked in Cambridge for 15 years on separating the systems there. Recently, the city’s mitigation efforts are planned during its annual pipeline rehabilitation program, “which fixes pipes before they break but in so doing reduces the amount of groundwater that enters the system,” Raiche emailed separately.

In coordination with the MWRA, the city changed its configuration of water flowing into the brook. Though both efforts were small in results, it was “carefully balanced (sic) as not to exacerbate the volumes at the Cambridge CSO locations,” speaking to the balancing act. Future transformations to the system “will be very complicated and will require coordination with MWRA and Cambridge,” because, for example, “much of the infrastructure to separate Somerville sewers would physically be located in Cambridge,” as noted in an email. A long-term control plan required federally is in the works with Cambridge and the MWRA. “Somerville has been gearing up for this effort since 2016. It’s just a really difficult problem to solve.”

Graphic depicting the sewage contamination at Alewife Brook CSO outfall. — Photo courtesy of Save the Alewife Brook

State data presented at the City Council meeting shows an 87% reduction in overall combined water volume, and 93% of the remaining volume is treated since significant work in the late 1980s and early 1990s. However, Anderson and her group claim 5,000 people live in the Alewife Brook’s 100-year floodplain and that for the past nine years, the average annual discharges have been double the allowed amount in a 2008 court case ruling. Other advocates like Green Cambridge and the Alewife Study group also want more action from the city, Cambridge, the state’s public water resources and transportation authorities, and the Department of Environmental Protection to comply with environmental regulations.

Under the previous administration, Mayor Joseph Curtatone was able to get a $700,000 loan for assessment and cleanup of brownfields, contaminated properties that cause environmental and public health issues. Somerville does not use any environmental protection agency funding for sewer projects, because of Somerville’s strong bond rating and low interest rates, Raiche said. “That may change if interest rates continue to increase,” and the city may apply for a state revolving fund program through the Department of Environmental Protection.

A unanimous city council ordered that he share the city’s approach and resources to get a combined sewer overflow on city borders with Cambridge and Arlington into compliance, after a presentation this spring by the local environmental advocacy organization with over 2,300 signatures of support.