*

Denise Provost is a member of the Somerville literary group The Bagel Bards. She is an accomplished poet, State Representative, and has done an infinite amount of work for establishing a Poet Laureate for the State of Massachusetts. Oh … yes, she is a great book reviewer too, as evidenced by her article below:

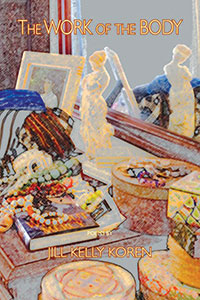

The Work of the Body

Poems by Jill Kelly Koren

(Dos Madres Press, 2015)

Review by Denise Provost

I confess that I’m drawn in by book titles, and that Jill Kelly Koren’s recent publication had me wondering, what is the work of the body? The cover art suggested a lush physicality: on a cluttered dressing table, a female figurine shown twice, its half-draped back mirror-reflected. Will the “work of the body” written here prove to be a hot-house hedonism?

The answer is that in these pages, work is work. Bodies fight gravity (“which never tires,” notes the narrator of Inside Out) – and they lose. They bleed, and age, and sicken. They muse, and mourn; they clear out the belongings of past generations, and they reproduce.

The epigrams in this volume make clear that Kelly Koren is singing the body electric, and that she means work in many senses, the literal sense being prominent. As if to establish the bona fides of her framing of this collection, the poet has arranged each chapter under a heading which is a law of physics. I confess I was concerned that this approach – frankly ambitious – might prove to be precious, or contrived.

Yet Kelly Koren pulls it off. Her poems, most of which are meditations on the small episodes of domestic life, manage to connect physicality and physics. They start with particular moments, like the butterfly emerging from a hollow shell in Winter Hatch:

My two-year-old son toddles toward it.

Don’t touch it, my brother warns.

I won’t, Sonny says…

…unaware that the Swallowtail

will not survive the week….

There is momentary interaction of these lives. The sun traces the passage of the hours, leaving the narrator “[t]ired of all the brilliance…,” and reflecting that, “[w]e are all on our way/to somewhere else.” This thought is so lightly expressed that it might as well be the Swallowtail.

Kelly Koren treads potentially treacherous territory in this book, populated with her children, parents, husband, extended family (living and not), and the imagined lives of others. A poem like Yard Sale Day, for instance, might have turned sentimental in less skilled hands:

The house where my father grew up

has upchucked its contents

onto the old horse field….

a life undone, bared for the hunters

of bargains to claim….

The poem, though, while tender, never becomes mawkish. It – and presumably the poet – inhabit a space where emotion can be laid bare and examined, but not distorted, or used for other ends:

He closes another deal,

then weaves his way back

through the forest of furniture,

voice low and serious now:

Don’t write a poem about this, okay?

It’s an impressive equilibrium to keep, and one that Kelly Koren boldly pursues. Some of us would only read “the latest mother-on-child/atrocity in the newspaper,” and shudder. Kelly Koren goes there, in The Ache, imagining infanticide from the inside:

Something has happened to my child!

She also means: something has happened to me.

I have done something

so unspeakable

that only prayer

or the edge of a knife

can answer.

She takes on a similar theme in Icarus Bounced, exploring the chemical (hence physical) disarray of post-partum psychosis:

What better way to kill

anxiety than to extinguish

its source? Spare the broken-winged

bird a life of low flight?

It occurs to me that one of Kelly Koren’s past lives, as a gymnast, might help explain her willingness to take risks in her literary work. Some of the risks she takes are with edgy material, but many of her risks consist of taking on topics so ordinary that they challenge preconceptions of what poems can be made of. For instance, The Work of the Body starts with the poem Tooth, Fairy, in which a six-year-old drops a pulled tooth down the drain:

I lose everything!

his sobbed refrain,

and I can do nothing but sit with him

on the red futon and marvel

at the completeness of his grief.

This poem’s epigram is from Elizabeth Bishop: “The art of losing isn’t hard to master.” Like the doomed butterfly in Winter Hatch, and the dispersed heirlooms of Yard Sale Day, teeth, and other body parts, and the mortal lives of generations keep proving themselves to be on their way “to somewhere else.”

“Faced with the prospect of moving,” somewhere else, the narrator of Green Atlas inventories every plant in an “unruly patch of Earth,” with pertinent advice:

Along the fence, you’ll find

Dwarf Arbor Vitae and holly

but the honeysuckle will take over

if you let it, and you might, just to

smell that knee-knocking sweet-sweet smolder…

The Work of the Body provides its own inventory, of sorts. The landscape of mothering, daughtering, nurturing, comforting, creating, and taking the moral measure of the world are all here. You may find that its unassuming poems do take over a part of your own consciousness, and smolder there long after you’ve put the book down.

Reader Comments